Serious debates about Nepal’s prosperity often begin in the wrong place—investment shortages, infrastructure gaps, or the absence of bold policy ideas. These diagnoses are comforting because they imply that prosperity is only a plan or a leader away. The reality is more uncomfortable. Nepal’s most binding constraint is not what it lacks, but how it is governed. The absence of rule of law has become a central obstacle to growth.

Rules Are Economic Infrastructure

At its core, the rule of law means that rules are transparent, applied equally, enforced consistently, and insulated from personal or political influence. In such systems, outcomes depend on what the law says—not on who one knows, which party one belongs to, or how aggressively one pursues informal channels to bend it. Rule of law allows citizens and firms to plan, invest, and take risks without fearing that outcomes will change at the whim of the powerful. In Nepal, however, power routinely overrides law, and unpredictability has become a defining feature of public life.

Closely tied to the rule of law are institutions—the courts, civil service, regulators, police, and other organs of the state—that translate written rules into real-world outcomes. In well-governed systems, courts resolve disputes fairly and on time; civil services apply procedures uniformly; regulators enforce rules rather than negotiate them; police protect citizens rather than power; and public agencies function independently of political cycles. Institutions matter because they constrain arbitrariness: where institutions are strong, individual power is limited by procedure; where institutions are weak, outcomes depend on who intervenes rather than what rules require. Nepal falls into the latter category, where power replaces rules and stagnation displaces growth.

Anyone who has dealt with public offices in Nepal recognizes the consequence. Progress depends less on meeting requirements than on finding someone who can intervene. Even basic interactions with the state—paying land taxes, obtaining citizenship certificates, or securing permits for small businesses—become obstacles rather than services. This is not a minor inconvenience; it is an economy-wide tax on time, effort, and morale.

Kathmandu School of Law wins 58th Jessup International Law Moot...

Nepal’s weak rule of law is not sporadic; it is continuous. Under the Rana regime, Nepal did not lack laws or courts; it lacked neutrality. Economic activity depended on permission and proximity, and courts served authority rather than citizens—rule by law, not rule of law.Under the Panchayat system, authority was centralized and often arbitrary, but institutional control was at least coherent. After 1990, democratic freedoms expanded, but institutions were politicized instead of professionalized. Transfers, promotions, contracts, and investigations increasingly followed party logic rather than written rules.

After 2008, fragmented authority further weakened accountability, dispersing power without strengthening enforcement. Constitutions changed, governments changed, but institutions did not strengthen. In fact, the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators show that Nepal’s performance on key measures of institutional quality—public service delivery, control of corruption, and the rule of law—deteriorated across the post-Panchayat period, with the sharpest decline occurring in the republican era.

Impunity Kills Motivation

Nepal’s problem is not the absence of laws, nor even—though sometimes this is true—the quality of the laws themselves. It is that enforcement is selective, outcomes are negotiable, and accountability is rare. The preferences of the powerful, rather than the rule of law, govern public life. In such a system, those who lack access to power—who cannot buy influence or refuse to seek it—find their aspirations blocked not by failure, but by a system that withholds opportunity.

When following rules offers no assurance of results, people adjust accordingly, seeking to influence or buy favor rather than putting effort into value creation. This behavioral shift is visible across the economy, including in the daily crowds that gather at the homes of political leaders, where access replaces process and rules are circumvented. The economic cost is not only corruption, but lost output: hours spent navigating power are hours not spent producing goods, services, or skills. This is a feature of a feudal system Nepal has never dismantled. Over time, this inversion does not just slow activity; it erodes motivation completely.

The economic damage caused by this system is immense, even if it cannot be neatly measured. Every delayed permit, every court case that drags on, every file that moves only after repeated visits or informal ‘follow-ups’ imposes a real cost on society. Time—a scarce resource—is wasted. As uncertainty deepens, risk premiums rise—not because markets are volatile, but because rules are unreliable.

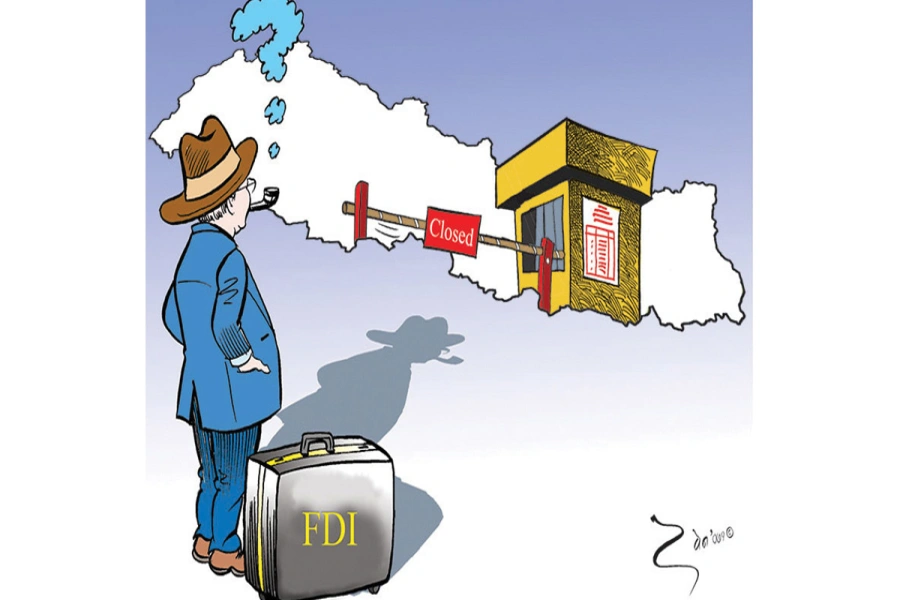

One of the clearest economic consequences of weak rule of law is the absence of company formation. Economies grow through the entry, competition, and expansion of firms. Nepal, however, has failed to develop a broad base of companies. A few large firms with strong political connections dominate multiple sectors, using influence to block entry, tilt regulation, and crowd out competitors. An economy without firms cannot generate growth, no matter how many plans it produces. As a result, job creation remains weak, competition is stifled, and productivity stagnates.

Weak rule of law also shortens economic time horizons. Long-term investments—factories, supply chains, skills, research—require predictability over years. When rules shift with political winds, capital moves toward activities that can be exited quickly. Trading, real estate, and arbitrage dominate over manufacturing and innovation. The constraint here is not a lack of resources, but uncertainty about whether rules will hold tomorrow. This is reflected in banks that are flush with liquidity but face weak demand for productive borrowing due to institutional uncertainty.

Weak institutions do not only drain talent through migration; they also misallocate the talent that remains. In an environment where effort does not reliably pay off, brilliant minds are consumed by maneuvering to navigate and manipulate the system rather than create value. The tragedy is not only that talent leaves the country, but that ambition itself is gradually extinguished among those who stay.

Power Over Law Means No Growth

As Chanakya warned more than two millennia ago, societies fail not because people lack morals, but because rules are weak, unevenly enforced, or selectively applied. When laws become negotiable and punishment depends on status—as has been the case in Nepal—corruption stops being exceptional and becomes rational behavior.

Nepal now stands at a hinge point. Prosperity will not come from slogans, plans, or budgets. It begins with the rule of law. Courts must decide on time, civil services must follow procedure, regulators must enforce rather than bargain, and accountability must apply without exception. Above all, ordinary citizens must be assured that the law works for them, not just for the powerful.

Rules are the foundation of prosperity. Abstract visions and grand promises are meaningless unless political parties accept this basic fact. Prosperity follows only when rules are applied consistently and power is restrained by law. Nepal must decide—urgently—whether it is ready to live by rules rather than rhetoric, and whether it is prepared, at last, to be governed by law.

The author holds a PhD in Economics and writes on economic issues in Nepal and Canada. He can be reached at acharya.ramc@gmail.com